Dekleptification—How USAID has fought corruption in Ukraine and elsewhere

6 Oct 2022 (Brookings.edu)

Dekleptification (noun): The process of uprooting entrenched kleptocratic structures—USAID

The enhanced USAID focus on corruption is reflected in its release in September of a trilogy of documents on anti-corruption—a draft “USAID Anti-Corruption Strategy”, USAID Guide to Countering Corrupton Across Sectors, and Dekleptification Guide. The latter is particularly interesting and timely.

The Dekleptification Guide is a program guide built on the knowledge and experience of USAID staff involved in anti-corruption programs in 14 USAID missions and compiled under the leadership of an outside policy expert serving an eight-month fellowship at USAID. The result is a compelling, informative, and frank report based on what USAID, other U.S. government agencies, NGOs, and various donors have collectively done over several decades of addressing corruption.

This innovative report is instructive for a broad array of audiences—USAID, development practitioners, in-country partners, policymakers, donors, and investigative journalists.

PROGRAM GUIDE

This program guide is a roadmap of how to “dekleptify” through what it identifies as three pillars of reform:

- Transparency—making public information on government officials’ assets, beneficial ownership of companies, and government procurement

- Accountability—putting this information and government spending in forms that are readily available, and supporting civil society and independent law enforcement agencies to hold public officials accountable

- Inclusion—opening the economic space by ending economic capture

The guide identifies three successive phases of political opportunities, or “windows”, to pursue dekleptification—Before the Window, During the Window, and After the Window. It outlines actions to be taken within each stage.

For example, “before the window” is the time to begin deep political/economic analysis and map the kleptocracy and how it functions, invest in civil society, and build relations with indigenous anti-corruption actors.

The guide goes into considerable depth and breadth in laying out actions for “during the window,” including 11 lessons learned and specific actions to be taken to institute the three reform pillars of transparency, accountability, and inclusion. It then identifies several steps to be taken “after the window” in order to support and defend reformers and call out incidents of backsliding.

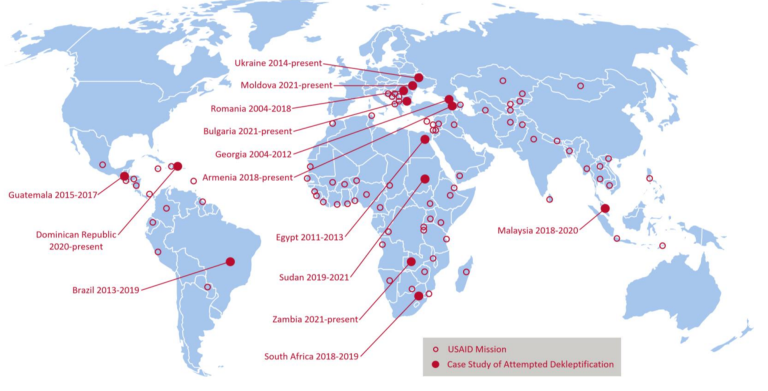

The map below shows the period the window was, or still is, open in the 14 countries. What stands out is that six of the countries are in the former Soviet Union, with the window still open in four.

Figure 1. Map of USAID missions and dekleptification windows

UKRAINE

The appendix on Ukraine, one of 25 countries out of 180 for which Transparency International reports an improvement in corruption over the past decade, is particularly timely. It draws a comprehensive and detailed picture of a decade of anti-corruption activities in Ukraine by USAID, other U.S. government agencies, donors, and local partners.

The appendix on Ukraine, one of 25 countries out of 180 for which Transparency International reports an improvement in corruption over the past decade, is particularly timely. It draws a comprehensive and detailed picture of a decade of anti-corruption activities in Ukraine by USAID, other U.S. government agencies, donors, and local partners.

Not to downplay actions on dekleptification that still need to be undertaken, but as a striking indication of the progress, among other transparency measures, Ukraine has the world’s:

- First public beneficial ownership registry

- Most transparent public procurement system

- First public database of politically exposed persons

- Most comprehensive and well-enforced asset declaration system

The story of dekleptification in Ukraine is not all roses. A hard lesson is that it is not enough just to secure the creation of anti-corruption governance bodies, but that civil society and reform actors must stay vigilant on how they are set up, staffed, and operated. As oligarchs seek to install their allies and otherwise stymie their operations, three of five specialized anti-corruption agencies lack permanent leadership. But Ukraine has adopted a truly brilliant safeguard system that calls on international expertise and credibility while honoring Ukrainian sovereignty and ownership—Ukrainian law now requires that judicial candidates for the High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC) must first be vetted and approved by the Public Council of International Experts.

SEE THE ORIGINAL ARTICLE