Iraqi Parliamentary Election 2021

By: Zuhair al-Maliki, with Jane Lott, Cole Plante, and Ashraf Bawer

A manual recount ordered by Iraq’s Independent High Electoral Commission (IHEC) is expected to change little in the outcome of the Council of Representatives (COR) elections held on Oct. 8 and 10, 2021. The distribution of seats may not change, but based on preliminary results, change is nevertheless coming to Iraq.

The recount order came after a review of 816 of the 1,436 complaints received by the Commission before the final deadline last week. The Commission has until Monday to complete its review, but thus far has found 26 complaints with sufficient evidence to justify a recount, including claims by some Iran-backed militia of being denied access to voting.

The parliamentary election, originally ordered by Iraq’s Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi for June, was forced by years of protests culminating in the ouster of former prime minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi in May. Since then, the election process has been marred by issues of corruption, complaints of fraud, and even removal of some candidates from the ballot, which nevertheless included 167 coalitions and parties and more than 3,200 candidates for the COR’s 329 seats, nine of which are reserved specifically for minorities.

Voter turnout, variously reported at 34-to-43 percent (depending upon the comparison), was the lowest of record since the democratic system was initiated by the U.S. in 2003. Many have attributed the low turnout to a form of mass protest again what is perceived as the continuation of a corrupt political system that does not serve the people.

Image Source: Al-Jazeera

Although preliminary totals have been announced, the IHEC has removed these numbers from its official website pending final results of the IHEC complaint process, including a recount in progress; and some disputes may be headed to the courts to resolve.

Nevertheless, no significant changes in the outcome are expected in what is an historic and significant election for Iraq.

Preliminary Results – Biggest Winners

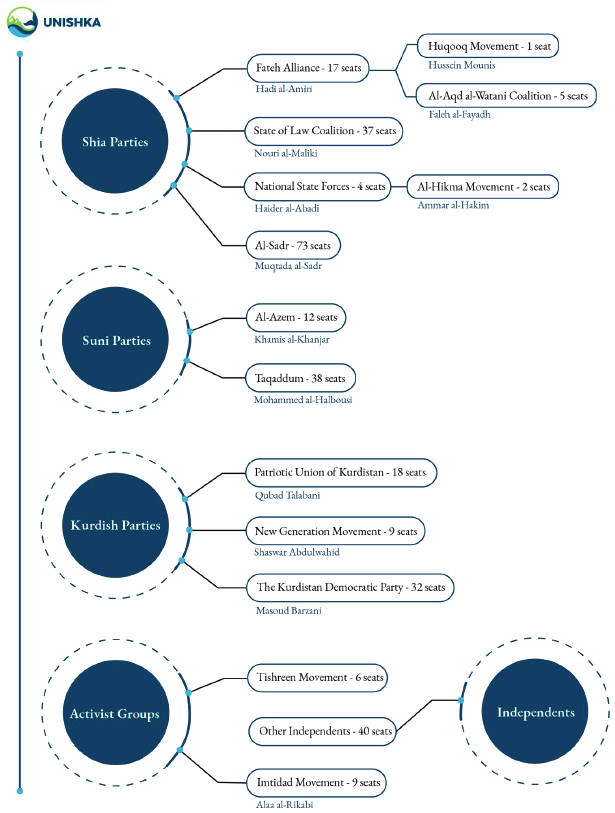

Preliminary election results show dramatic changes in the composition of the COR as compared to 2018. Although no party won an outright majority, the Sadrist Movement, led by populist Shiite cleric Moqtada Al-Sadr, came away with 73 seats, or 22 percent of the COR. This marks a gain of 19 seats over the 2018 elections, when Al-Sadr’s Saeroon alliance won 54 seats. This increase is attributed to either strategic campaigning, low voter turnout, or fraud, depending upon the source.

Coming in second behind Al-Sadr, Sunni Parliament Speaker Mohammed Al-Halbousi’s Taqadum group won 38 seats, and close behind with 37 seats was the State of Law Coalition, led by former prime minister Nouri Al-Maliki. The State of Law Coalition showed an impressive gain over its 25 seats of three years ago.

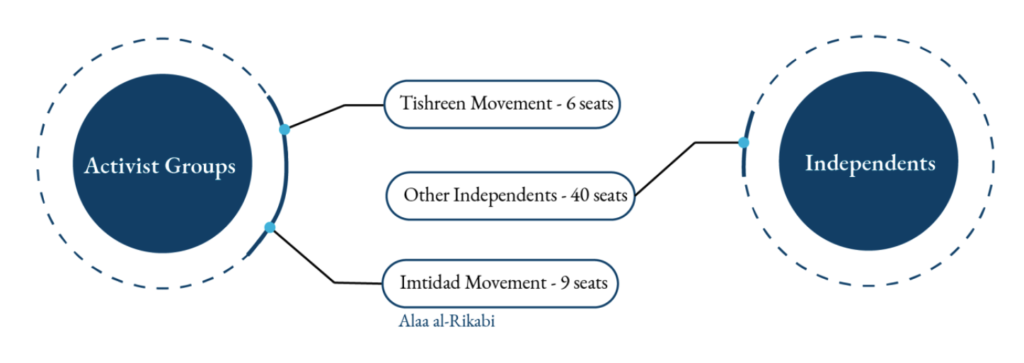

Independent reformists, notably those that emerged from the 2019 protest movement, also scored impressive wins: Imtidad winning nine seats and Kanoon, six. As a group, activists and independents may account for the second largest bloc in the COR, assuming they work together.

Activists and Independent Seats

Preliminary Results – Biggest Loser

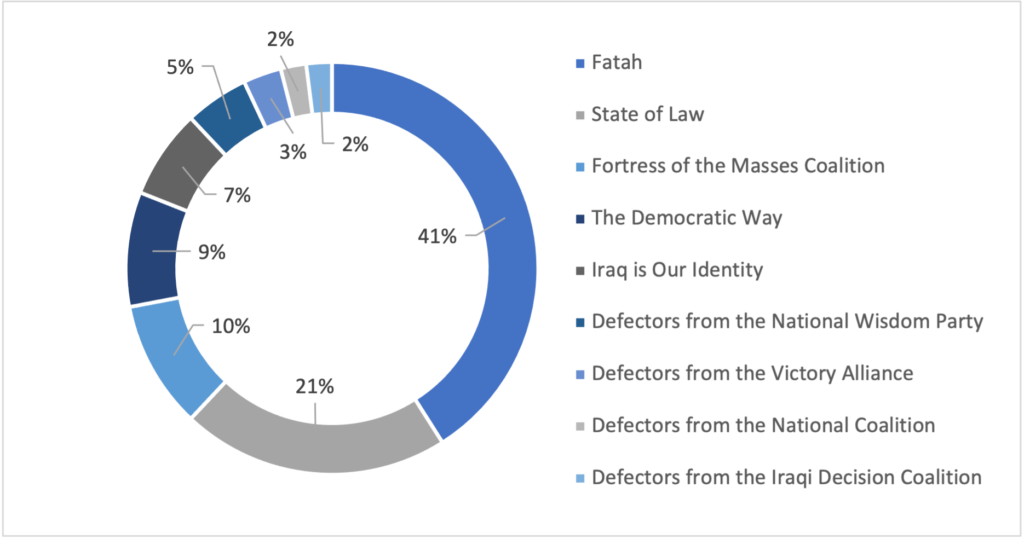

While Shia parties led by Al-Sadr and Al-Maliki scored substantial gains in the COR, Shia groups backed by Iran – notably the Fateh (Fatah) Alliance, headed by paramilitary leader Hadi Al-Amiri – lost dramatically, from holding 48 seats in 2018 to only 17 after the 2021 election, not including the minority Christian seats.

Not surprisingly, the strongest complaints to the 2021 parliamentary election results come from this group, which also includes the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), aka Popular Mobilization Units (PMU).

The alliance said in a statement that it has rasied “technical observations” about the vote. These pro-Iranian militias claim – not without some justification – that they were denied by government officials of the right to vote.

The recent parliamentary elections were held on two days: October 8 for Iraqi security forces, displaced persons, hospital patients, and prisoners; and October 10 for the general public. Allowing the police and soldiers to vote ahead of the general election was intended in order to provide security on election day.

According to some sources, when Iranian-backed militias attempted to vote on Oct. 8, they were refused on the grounds they were not a state security force. They appealed.

On the second day of voting, Oct. 10, when these same pro-Iranian militias attempted to vote, they were denied on the grounds that, their appeal having been accepted, they were deemed security forces and consequently, should have voted on Oct. 8.

Moving Forward

Whether or not evidence or a recount supports the Fateh contention of fraud, the issue and others will no doubt be headed to the courts. But the dramatic loss of seats by Iranian-backed parties and the plurality gained by Al-Sadr show a marked trend towards nationalism, if not just reducing Iranian and United States influence in Iraqi politics.

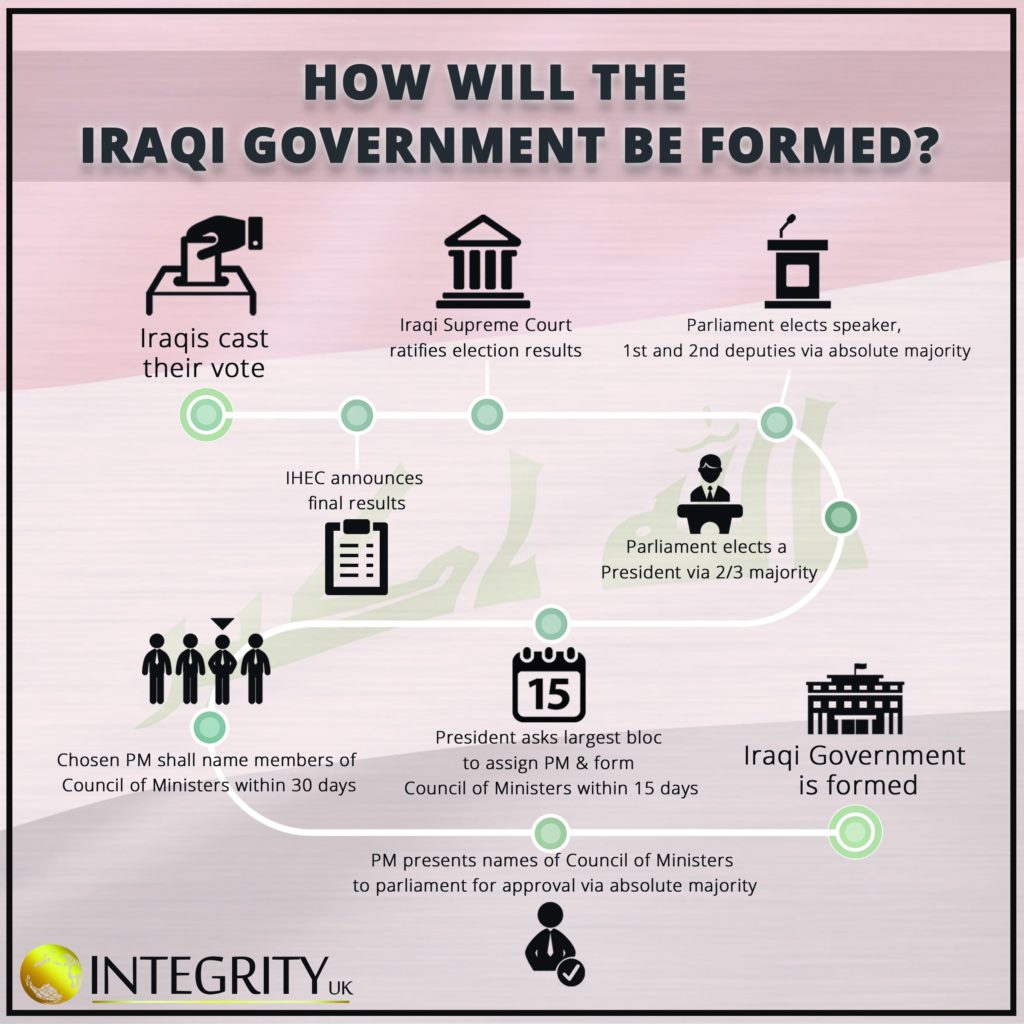

In the meantime, coalitions are already being formed in order to create a majority bloc required to nominate Iraq’s next prime minister, president, and cabinet members.

It being statistically almost impossible for any one candidate to win the +164 majority required to control the COR, the government is still up for grabs. Al-Sadr, who ran on a nationalist platform and who won the plurality of votes, will be central to the parliamentary majority.

Still, it is unlikely the Fateh would be excluded in any future administration as doing so would invite conflict, including potential violence. In the past, Al-Sadr and Al-Amiri have cooperated to form a government.

Times have changed, though, and the introduction of independent reformist candidates, especially such a large number of them, will undoubtedly have a strong influence on the distribution of power in the new Iraqi government.

An even stronger influence will be the Kurds, who garnered 50+ seats between the two dominant parties, the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) – which added eight seats to its 25 from 2018 – and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). Since 2005, no Iraqi prime minister has been elected without Kurdish backing, and that is unlikely to change since even Al-Sadr needs at least 92 seats to form a majority.

But the illusion of Kurdish “unity” is showing cracks, especially as regards to the PUK, which is even more divided after Bafel Talabani became the sole chairman. This infighting may also lose the PUK the presidency, which is has held since 2005.

Image Source: Integrity UK

One factor in the Iraq elections that has gone oddly unremarked from an outside point of view is the potential power of the 97 women who won seats to the COR. This is the first election in Iraq’s history in which a minimum of 25 percent, or 83 seats, are allocated specifically to meet the women’s quota. In addition, political parties are required to have at least 25 percent women candidates. That women won almost 30% of the COR could make them, with the right leadership, a force to be reckoned with, all other things being equal.

But change takes time, and change that holds comes slowly. The current changes in Iraq will be a matter of striking a balance with international interests and of solving domestic problems, such as food and electricity distribution. Revolutions begin when people are hungry.

In the meantime, it appears that in Iraq, change is coming – albeit very slowly.

What to Expect

In the weeks to come, leaders of all parties will be focussed on forming a coalition capable of electing a prime minister.

While Sadrist leaders have declared for months that the prime minister will be Sadrist, Fateh has claimed it will nominate one of theirs; there is much negotiation for someone between the two extremes. This man (Iraq is still a patriarchy) must be acceptable to Shia, Sunni, Kurd, and other parties, as well as to Iran and the U.S., both of which still maintain influence in Iraqi politics.

Potential Candidates

*Hover over the images to learn more

Former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki

His State of Law group garnered half the seats of the Sadrist Movement. He presented himself as the ideal leader to mediate between Iraq and the powers in Washington, D.C. and Tehran. And while he does have experience as prime minister (2006-2014), the trend in the last two election cycles has been for a compromise prime minister, one who is not head of a specific political party. His past U.S. support may impede his nomination, given the nationalism trend that has emerged from the 2021 election.

Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi

He became prime minister after the resignation of Adel Abdul Mahdi following months of protests in Iraq in 2019. That Al-Kadhimi has already met protesters; demands of an early election may garner their support. It also appears Al-Kadhimi has recently begun to get Covid-19 under some control. However, Al-Kadhimi’s association with the U.S. may be an asset – or not. In the Middle East, the more things change, the more they remain the same.

Iraq’s ambassador in London, Jaafar Al-Sadr

He has been discussed for months as one of the leading contenders for the position of prime minister. He is popular among the Sadrist party. Once a Member of Parliament, he resigned in 2011 in protest of corruption, and it has been claimed that he would refuse the nomination.

Provisional Outcomes as of Oct. 18, 2021