Political and Electoral Integrity Program

Political Finance Integrity

Political corruption, in which political actors are captured by large-scale private sector interests and/or are not allowed to compete on a level playing field due to abuse of state resources, is often the result of inadequate regulation of money in politics. Political finance (i.e., both campaign finance and political party finance) controls can increase accountability of political contestants and elected officials. Features of effective political finance systems often include: 1) disclosure, 2) public funding and subsidies, as well as guaranteed media time, 3) contribution and expenditure prohibitions, 4) contribution and expenditure limits, 5) campaign time limits, and 6) oversight, compliance, and enforcement. Comprehensive, detailed, regular, and timely disclosure is the foundation upon which a transparent and accountable political finance system is built. To identify the effectiveness of these features, it is critical to understand the existing legal and regulatory framework, a country’s readiness for reform, and the capacities of state and non-state actors.

Catalyzing Reforms

Political finance systems are built over time. Reforms require political will and an enabling environment such as a political finance scandal which is often a driver for reform. Reforms are also best taken in the period between elections and not immediately before an election. In order to identify and report on such scandals, investigative journalists need to understand the role of money in politics. It is also important for reformers to identify and seize these windows of opportunity to facilitate collaborative, trust-based relationships and build consensus among key stakeholders – legislative champions, political finance regulators (PFRs), political actors, civil society groups, media, academics, and, ultimately, the public.

Legal and Regulatory Framework

Once the purpose of the political finance system is identified and defined, it is important to work with legislative champions and regulatory bodies to review and support legal, regulatory, and procedural reforms. Such reforms are often grounded in developing an affective disclosure regime. Disclosure, particularly if public, generates greater accountability to the voters by encouraging more informed decision-making and political debate. Further, it encourages compliance with applicable laws and regulations by providing regulators with the political financial account information to enforce the laws that define the features of the system and better apply public funding mechanisms.

Political Finance Regulatory Institutions

It is also critical to support independent institutions for effective oversight, monitoring, and enforcement by working with PFRs such as election commissions, audit agencies, and other similar bodies tasked with implementation and enforcement of political finance laws and regulations. In so doing, their capacities can be built through training, mentoring, and technical assistance to support their operational and financial independence.

Compliance, Oversight, and Enforcement

To ensure appropriate, timely, and fair enforcement, political party agents need to comply with the laws and regulations, and prosecutors and judges need to understand the political finance regulatory systems. Doing so allows the latter to effectively work with PFRs, particularly auditors, to identify and address transgressions through prosecution or other remedies (e.g., fines, arbitration). Further, non-state actors in civil society and the media can use disclosure and other means (e.g., expenditure counting, tracking abuse of state resources) to monitor political finance, hold political actors to account, and educate the public

Political Finance Reform

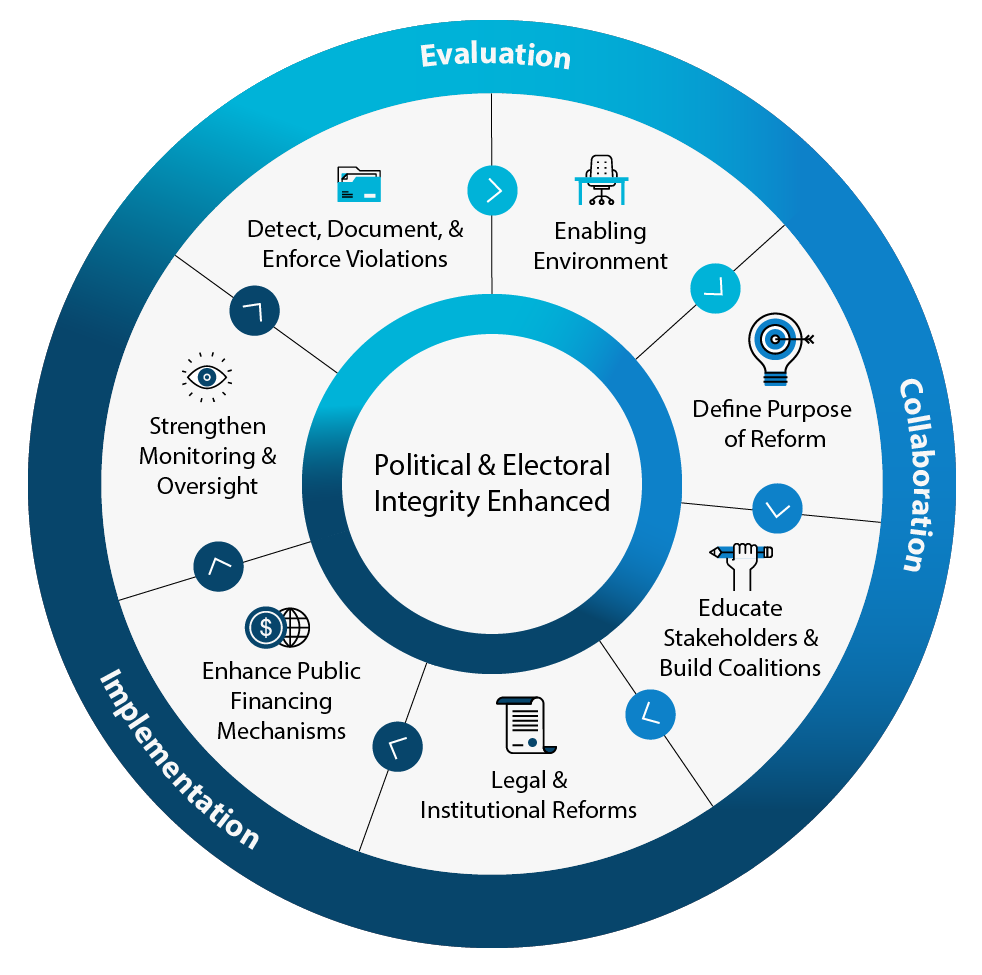

Reform requires a feedback loop that starts with an enabling environment (i.e., window of opportunity) which recognizes the political finance priority and encourages key stakeholder to assess and analyze the current state of the political finance system, and ends with an evaluation of the political finance system once the dust settles from an election. Working with a coalition of political finance stakeholders can bring about greater transparency and accountability among electoral contestants and politicians tasked with reflecting the will of the people.

UNISHKA's Approach

Through technical assistance, training, and mentoring, UNISHKA supports coalitions of political finance stakeholders to ensure greater transparency and accountability during each step of the Reform Cycle. To do this, we:

Conduct Political Finance Assessments

UNISHKA conducts assessments that analyze the legal and regulatory framework, readiness for reform, and institutional capacities, while mapping out political actors and civil society.

Train investigative journalists

UNISHKA trains journalists on the role of money in politics and in how to identify and report on political finance scandals in an accurate and impartial manner.

Identify and seize upon windows of opportunity

UNISHKA identifies and seizes windows of opportunity to facilitate collaborative, trust-based relationships and build consensus among key stakeholders – legislative champions, political finance regulators (PFRs), political actors, civil society groups, media, academics, and, ultimately, the public.

Conduct collaborative multi-party, political finance stakeholder workshops

UNISHKA conducts workshops to define the purpose and direction of political finance reforms by examining comparative practices from other countries facing similar challenges.

Review and support legal, regulatory, and procedural reforms

UNISHKA reviews and supports reforms by providing comparative practice, model laws, and technical advice to legal reformers and regulatory bodies.

Introduce transparent political finance account disclosure, asset disclosure, and review and audit mechanisms

UNISHKA introduces disclosure, review, and audit mechanisms through technical assistance and digital solutions.

Provide comparative practice guidance

UNISHKA provides this guidance in the introduction or enhancement of direct and/or indirect public subsidies for political parties and candidates.

Collaborate with local civil society partners

UNISHKA collaborates with local partners to conduct monitoring of routine political party and campaign finance account information.

Promote effective oversight, monitoring, and appropriate, timely, and fair enforcement

UNISHKA promotes oversight, monitoring, and appropritate, timely, and fair enforcement among PFRs and the judiciary by training and mentoring political party agents in compliance, and prosecutors and judges to better understand the political finance regulatory systems.

Political Finance Reform Cycle

UNISHKA Talent

Jeffrey Carlson

Vice President, Programs & DevelopmentJeffrey Carlson is a democracy, governance, and integrity professional with 27 years of experience. He possesses on-the-ground, comparative practice in over 30 countries, including non-permissive and conflict-prone environments, and nascent and consolidating democracies. He is a subject matter expert, thought leader, analyst, and trainer experienced in assessments, knowledge enhancement, skills transfer, and capacity building of government institutions, media, and civil society. Currently, as Vice President at UNISHKA Research Service, he specializes in combating political corruption by promoting transparency and accountability in political finance, and government and civil society oversight. Previously, he improved democratic and electoral practices by serving as founding director of the Electoral Education and Integrity Practice Area at Creative Associates, establishing the program on political finance and public ethics at IFES, and coordinated electoral observation missions at the OSCE PA. He holds a BA in International Studies from the University of Washington and an MPM in Public Policy from the University of Maryland, College Park.

Monalee Teves

SME – ElectionsMonalee Teves has more than 20 years of significant work experience in the multi-sector settings of private corporations, media, government, and non-governmental organizations in more than 20 countries. She has extensive experience in governance and anti-corruption initiatives. She has served as the Acting Director for Transparency International-Philippines and as a National Program Advisor for the Transparency International Secretariat in Berlin. She has published more than 15 articles and is fluent in several Malayo-Polynesian languages. Monalee has earned a Bachelor of Arts in Mass Communications from the University of the Philippines and her Masters Degree in Development Practice from the University of Arizona. Monalee is also a graduate of the International Anti-Corruption Summer Academy (IACSA) in Vienna, Austria.

Illustrative Project Experience

USAID – Iraq

Working directly with the Office of the Inspector General at the Ministry of Health, UNISHKA developed a process for managing corruption complaints; mapped the distribution of medicines and medical supplies while providing contextualized recommendations; and increased transparency in the procurement processing.

ISAF/RS – Afghanistan

Working with the High Office of Oversight and Anti-Corruption (HOOAC), UNISHKA documented extensive corruption at the Dawood National Military Hospital in Kabul, primarily in procurement and acquisitions. This documentation formed the basis of a criminal investigation by the Office of the Attorney General and prompted an overhaul of their procurement processes.

OECD – Ukraine

UNISHKA’s Team Lead for Corruption & Healthcare, Drago Kos, currently serves as a member of the Selection Committee for identifying a new Head of the Special Anti-Corruption Prosecution Office (SAPO) in Kiev. He is also a former member of the International Anti-Corruption Advisory Board (IACAB) in Ukraine (2017-2019), and the former Co-Chair of the Ukraine Defence Corruption Monitoring Committee (NAKO) (2016-2019). In each one of these positions, Drago has also been involved in the Ukrainian healthcare sector addressing the nexus between corruption and healthcare. In his position in the IACAB he advised the Parliament of Ukraine (Verkhovna Rada) on drafting of drafting specific healthcare legislation. Additionally, in his position as Co-Chair of the NAKO, Drago forced the adoption of a report on the procurement and distribution of medical equipment and pharmaceuticals, directly initiating stronger internal controls for purchasing and tracking medical equipment and drugs.